In the Fall 2010 semester the Lab will explore the essential functions of the museum with the aim of inverting the traditional museum program and identifying new ways of making its internal processes of collection, conservation and interpretation more accessible and socially engaging. As evident in a range of recent projects, museums are increasingly interested in making their internal processes transparent –even participatory– for their visitors through on-the-floor staff interactions, visible study collections, interfaces to digital resources and the use of social media. These techniques and technologies allow museums to explore and even to blur the boundaries between ‘front of house’ and ‘back of house’ functions and afford new ways for the museum to connect with its audience.

In the Fall 2010 semester the Lab will explore the essential functions of the museum with the aim of inverting the traditional museum program and identifying new ways of making its internal processes of collection, conservation and interpretation more accessible and socially engaging. As evident in a range of recent projects, museums are increasingly interested in making their internal processes transparent –even participatory– for their visitors through on-the-floor staff interactions, visible study collections, interfaces to digital resources and the use of social media. These techniques and technologies allow museums to explore and even to blur the boundaries between ‘front of house’ and ‘back of house’ functions and afford new ways for the museum to connect with its audience.

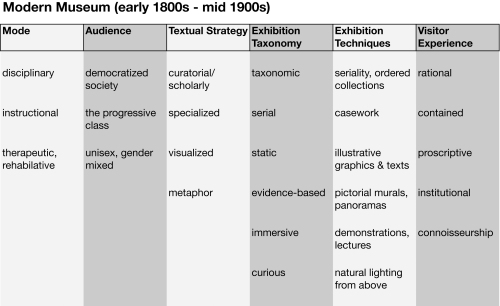

The American Association of Museums (AAM) defines the museum as being comprised as a set of specific activities that are conducted under a guiding mission. These include: collection, conservation, interpretation, education, and exhibition. Unless we are museum professionals working within an active museum, most of our attention as members of the public is traditionally focused on exhibitions, and perhaps occasionally on an educational event or program. The first three activities listed represent for most of us that mysterious hidden world behind the gallery walls and are often misunderstood, or at the very least under-appreciated while the activities of collection, conservation and scholarship are essential to any museum. Some might even suggest that there is a subtle institutional progression implied in this list of activities that places them in a linear hierarchy with the first – collection – being somehow the most essential and the last – exhibition – being almost an operational burden.

It goes something like this: if you do not collect there is nothing to conserve. Scholarship and interpretation requires an object of study. If you do not have scholarship then you cannot teach and if finally you do not have anything unique to say then what will your exhibition hope to communicate to its visitors? That may be a bit rash but you get the point.

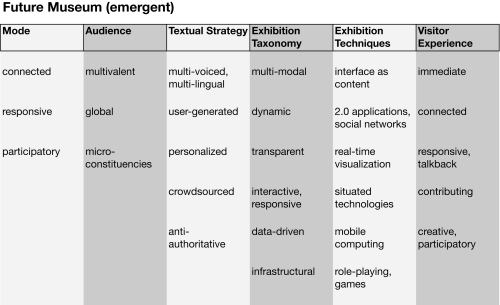

Historically the systems of collecting and interpreting natural, cultural and artistic heritage have indeed informed the development of a museum’s architecture, its exhibitions and public programs. As systems of collecting and the construction of knowledge have changed over the last two centuries, we have seen corresponding changes in museum architecture, exhibition and programming. We will explore how these changes played out in the museum, what societal forces drove the changes, and how design and museum practices have responded. We will identify emergent approaches in a range of new and existing museums. We will look at architecture, exhibition, technology, media, and the role of the curator and designer in shaping museum experience.

I am in interested in weaving together a number of disparate threads that I believe are catalyzing in this shift toward making the museum’s ‘back of house’ increasingly visible and essential to connecting with their visitors. After a decade characterized by iconic museum buildings and expensive permanent exhibitions and the subsequent decline of philanthropic support due to the downturn in the economy, museums are now looking hard at ways of making more value out of their existing assets. Back of House aims to explore this trend across at least three modes of implementation: the physical, the personal and the digital.

Themes and Threads

Architecture Inside Out

Over the last 50 years there has been a dramatic change in museum architecture. Long gone are the vaulted, naturally lit galleries of the early 20th Century and the ideals of symmetry, solid masonry walls, steep stairs and pillared portico entries. Modernism brought a disciplined rationality to buildings that were optimized for flexibility, flow and operational performance. Postmodernism was marked by what we might be called narrative architecture. These are buildings that are purpose-designed to a specific text and meant to convey a specific story. Now, at the culmination of a museum building boom that lasted almost 20 years, there is a new trend emerging. In museums both recent and currently underway we are seeing an opening up of buildings, deconstructing the formality of the gallery, extensive use of glass and day-lighting, dramatic views both inside and beyond the walls of the museum, views into research areas, visible storage, study centers and high density collections displays, and a hybridization of traditional museum program or ‘nested’ programs where learning laboratories and other facilities are literally embedded within the gallery. The Luce Foundation sponsored study centers at the Smithsonian, Metropolitan Museum or the Brooklyn Museum are examples of this approach. Another example might be the London Museum of Natural History’s new Darwin Centre—a multistory, light-filled building attached to the original neo-gothic structure of this venerable museum, like a cocoon that opens to reveal the scientific research and collections functions of the museum to the visiting public.

Status of the Object

The second theme we will explore is the status of the physical object in museums. While this will not be a class on materiality or material culture, we will explore the role of the museum collection as it relates to the function of the museum, conservation, interpretation, and exhibition. Recent publications such as Sherry Turkle’s Evocative Objects or historian Stephen Conn’s Do Museums Still Need Objects? explore the status of the analog object in the age that appears to favor the digital medium. The title of Conn’s book is striking. In fact it is almost alarming. Conn is a scholar and has spent a career rigorously mapping the changing topography of the museum as it responds to nuanced changes in society. The title is very direct and implies that an urgently needed, practical discussion will follow. The fact is that there are many, and perhaps even an increasing number of museums without objects. What is at stake in this trend?

Social Networks

The third theme concerns the advent of social networking applications and the integration of technology into the museum experience and the consequent “decline of the expert.” The ubiquity of social networking applications may be a symptom of society’s constant search for order and empathy that has been enabled and made visible by new technologies. At the very least, it reinforces the increasing importance we place in the definition of the Self as we seek to clarify and document our unique worldview, while at the same time atomizing into online micro-communities of like-minded individuals. We define ourselves by the connections we make in social space and the things we collect and give preference to. Museums have also traditionally facilitated this. The boundaries between traditional roles, responsibilities and authorities have shifted. We are now simultaneously content producers, curators and consumers. Museums are exploring ways to incorporate user-generated content and participatory experiences where the visitor becomes integral to the production of the experience. The scholar’s voice is just a starting point. In some cases it does not exist at all. The visitor’s voice joins a cacophony of others to form an infinite number of meanings where the project of interpretation is never finished. Nina Simon’s new book The Participatory Museum explores these ideas in depth and is sure to become a staple for museum professionals for the years to come. Other projects like steve.museum explores ways that social tagging can enhance the public assess and use of museum resources. What do these new social networking tools and digital assets provide to museums as they seek to communicate with our public? What does this mean for the role of the curator, scholarship and education in the museum?

Museum as Muse

Lastly, and more so than any architect or museum design professional, I am deeply motivated by a number of artists who actively use museum architecture, collections and processes as a site for their art. David Wilson’s LA-based Museum of Jurassic Technology; Ilya Kabakov’s immersive, and sometimes intentionally unfinished art gallery installations; Sophie Calle’s documentary approach utilizing photography and objects as evidence of a grand narrative; Andrea Fraser’s unauthorized, although seemingly ‘official’ museum tours; Mark Dion’s use of traditional archeological and forensic sciences and mock expeditions in unexpected places; filmmaker Peter Greenaway’s “100 Objects to Represent the World” and interactive room-sized talking painting “Wedding at Cana” at the last Venice Biennale; are just a few that come to mind. We will explore these works of art and see what they might teach us and ways of visually expressing the essential activities of the museum.